A

Fill is a repeated run stitch back-and-forth in rows, used to cover a large

area. There is a lot of terminology associated with fills, such as “complex” (it

can have holes), “Tatami” or “Ceeded” (The runs are offset so the rows don’t

line up), “Edge Travel” (the stitches run along the edge instead of under the

rows), etc.

A

Fill is a repeated run stitch back-and-forth in rows, used to cover a large

area. There is a lot of terminology associated with fills, such as “complex” (it

can have holes), “Tatami” or “Ceeded” (The runs are offset so the rows don’t

line up), “Edge Travel” (the stitches run along the edge instead of under the

rows), etc.

The main issue is density, or the distance between rows, and

here is where you get to make a decision. When a fill executes, it puts a lot of

stitches into the fabric. Those stitches displace the fabric somewhat, just like

when you get into a bathtub, the water has got to go somewhere – stitches in

fabric are the same. So the more stitches you put into the fabric, the ‘bigger’

the fabric has to become to handle it.

Remember that density is measured in stitch points, which are

tenths of a millimeter. The bigger the distance, the lower the density.

In the past, the typical production method was to use a

cut-away stabilizer that can hold together with a lot of stitching in it, which

relieved the fabric considerably. Then, the designer could use densities of 4

points or even tighter, thus creating “full coverage.” Full coverage means

the fabric does not show through. It sounds good and if you’re being paid by the

stitch, it is great. But what if you want the fabric relaxed, not stiff as a

board? And full coverage isn’t as important as wearability and softness? Then

plan on releasing some of the density. Go for 5 point density or even lower.

There are other options too. Using two fills, in

different directions, but each with only half the density, you can create a far

more stable fill with less displacement. And the coverage works out quite

nicely.

If your fill sews out like a soup bowl, indented and firm, you

needed less density and more stabilization.

When a fill executes, it does so in sections. This is driven

by the shape of the object, and where the Exit point is located. When the fill

has to travel between those sections, it can either run under the rows of

stitches that haven’t been filled yet, or it can run along the outside edge of

the shape.

If the fill is a normal density, even, one of the lighter ones

previously discussed, the traveling runs probably will not be visible and

certainly not noticeable, so the most efficient thing to do is let the fill

travel normally.

There are uses for fills that have much wider spacing between

rows; trapunto effects for example. In a fill that has low density – where the

stitches are really far apart -- you may want the traveling stitches to go along

the outside of the shape, rather than under the rows where they would interfere

with the desired visual effect. This is accomplished by checking the ‘Travel

edge” box.

A fill has a single angle at which it runs. You can add an

inclination using the Incline button on the Tool Pane.

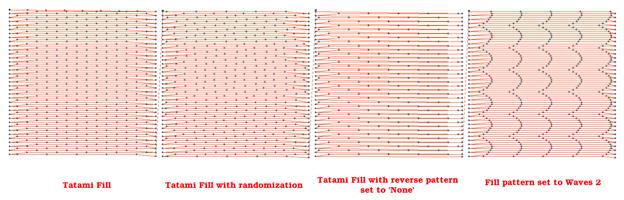

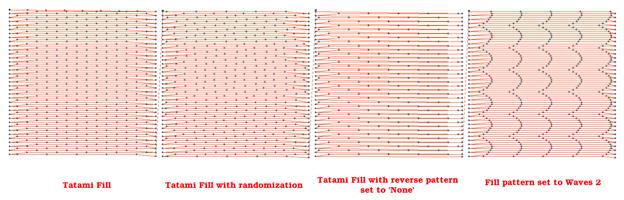

When choosing the patterned topstitch, a normal fill (tatami)

is the default, however you can adjust the pattern to have needle lands that

form texture. Each pattern can have its stitch properties adjusted. Stitch

Length in the pattern relates to the size of the pattern that is made. If you

make your pattern too wide, it will not be visible unless the shape itself is

wide enough. To make a fill appear smoother you can also add randomness to the

needle lands for a Tatami fill.

Note: There is also an option of

using fill pattern “None” which will emulate a satin. This is for very small

areas, where the stitches will not be excessively long, or for fills that are

only going to be carved.

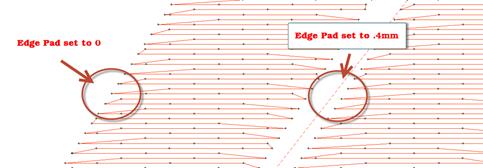

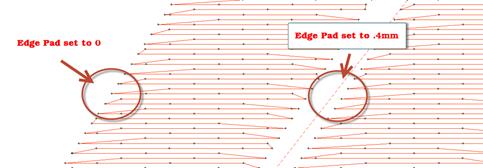

The Edge Pad is a means of protecting the edges of the

stitches from have excessive needle penetrations that can pull on the fabric and

pucker.

When patterning, the needle penetrations can lie next to one

another causing the fabric to lash or even cut. If this is a danger for the

fabric being embroidered, set the “Reverse” to “None” which means the pattern

will only occur on every other stroke of the satin. The pattern effect will be

lighter, but the embroidery will be better and the fabric will not have as many

cuts.

Compensation in fills is very similar to compensation on satin

columns, which has been described earlier. Unlike columns, however, there is

rarely a need for extra control such as side selection or push.

Compensation in fills is very similar to compensation on satin

columns, which has been described earlier. Unlike columns, however, there is

rarely a need for extra control such as side selection or push.

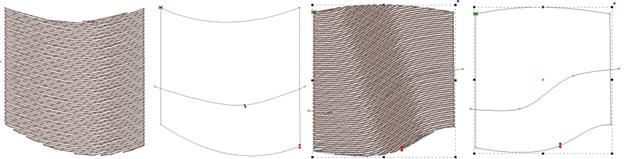

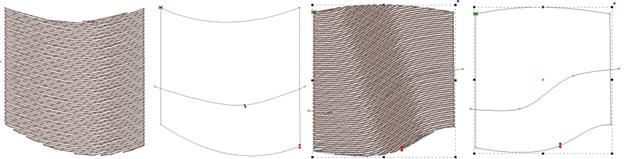

Fills can have curved rows of stitching, not only straight

ones. Switching to a curved fill is done with the “Curved” checkbox. When you

select the fill to be curved, a curved line, similar to a break line, will be

created for you automatically, and it will be angled as your inclination was

previously.

You adjust the curve as you would with any line. You can add

points and remove them. The curve is fully adjustable, but realize there are

some rules you should follow.

1. The

endpoints of the curve should go past the edges of the shape.

2. The

curve needs to be simple – making a loop may be fun, but it won’t be nice to

sew.

3. Hard

turns will give you areas of low density on the angle, and high density as they

straighten out, so use things like that with low density as second fill, for

texture and dimension.

Here are some examples of curving fills in action. The

stitches and the outline are shown side-by-side for each. Notice the curve on

the right has an additional node added to produce an ‘S’ curve:

When you click off the curved fill, the line will be replaced

with an inclination.

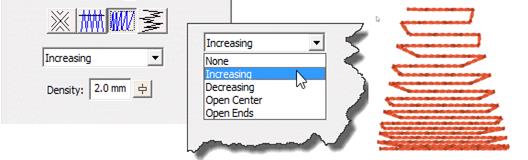

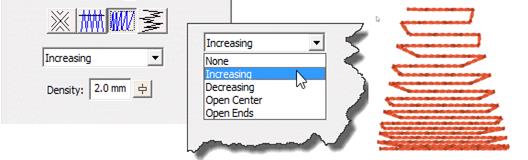

Gradient (Level 2)

The density of the fill can be adjusted so that each line of

stitching moves farther apart from the previous line, which makes for a varying

density, called a “Gradient.” Gradients are an effect, and not used to provide

coverage as a regular fill might. When making a gradient, you have two

densities; the starting density, which is the one set for the fill, and the

final density, which is the one set in the Gradient property. The gradient can

have different styles selected using the list box. Note that a standard fill has

a gradient set to “None.”

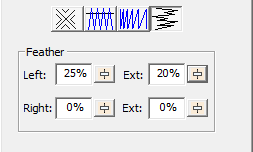

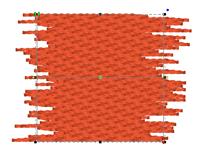

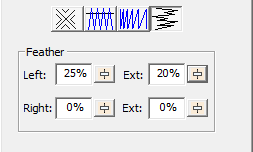

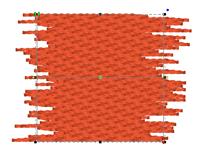

Feathering is the extending and shortening of the edges of the

fill in a random manner. This is used in fills that are adding texture to a

design, and generally would be used over some other design objects for

coverage.

You can adjust independently the left and right inside

feathering and outside feathering values. By feathering the edges, you can

create simple fur effects.

When setting feather options, realize that left and right are

subjective, and if you edit the outline after making this setting, those could

actually switch.

A

Fill is a repeated run stitch back-and-forth in rows, used to cover a large

area. There is a lot of terminology associated with fills, such as “complex” (it

can have holes), “Tatami” or “Ceeded” (The runs are offset so the rows don’t

line up), “Edge Travel” (the stitches run along the edge instead of under the

rows), etc.

A

Fill is a repeated run stitch back-and-forth in rows, used to cover a large

area. There is a lot of terminology associated with fills, such as “complex” (it

can have holes), “Tatami” or “Ceeded” (The runs are offset so the rows don’t

line up), “Edge Travel” (the stitches run along the edge instead of under the

rows), etc.

Compensation in fills is very similar to compensation on satin

columns, which has been described earlier. Unlike columns, however, there is

rarely a need for extra control such as side selection or push.

Compensation in fills is very similar to compensation on satin

columns, which has been described earlier. Unlike columns, however, there is

rarely a need for extra control such as side selection or push.