Creating corners with satin columns is a bit of an art. When

creating lettering for example, the cornering methods you use will radically

affect how the viewer of the stitched item perceives your embroidery.

The

simplest form of cornering is to simply turn, with inclinations going around the

turn. When making a hard corner, this results in stitches pivoting around the

inside corner of the turn. If you’re going to turn this way, try beginning to

‘lean’ the stitches into the turn, and when coming out of the corner, give them

some chance to ‘lean back up.’

The

simplest form of cornering is to simply turn, with inclinations going around the

turn. When making a hard corner, this results in stitches pivoting around the

inside corner of the turn. If you’re going to turn this way, try beginning to

‘lean’ the stitches into the turn, and when coming out of the corner, give them

some chance to ‘lean back up.’

Surprisingly, most of the time, professionals prefer to simply

turn corners instead of using more complex corner styles, which we’ll describe

next.

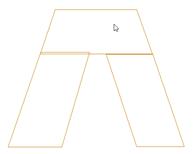

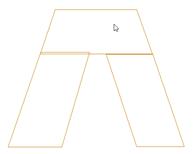

Letters often look better with a set of satin columns, rather

than turning around hard angles. One method commonly used is with three satin

columns: and entry, and end ‘cap’, and the exit stroke. A typical example is

this letter ‘A’:

You’ll see that the cap angle is as ‘flat’ as it can be so

that the stitching is smooth. For registration purposes, you may want to overlap

the cap on top of the entry column. And the exiting column usually is best to be

snug against the cap. In the illustration on the left, notice the slight overlap

of the left column and the cap – barely a stitch is typical.

A hard corner may not be appropriate for a cap. And it may be

so tight that it cannot turn reasonably. In this case, break the column into two

and overlap the corner. Don’t worry about the stitches overlapping each other,

as satin stitches sew quite well even when overlapped. If the density is not too

tight for the thread and fabric, you can even get a blended look.

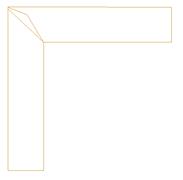

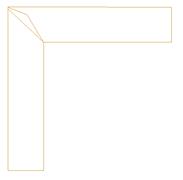

Mitering

Mitering is a form of overlapping where the exiting column

starts at a ‘point’ and widens out as it leaves the corner. This makes the

stitching resemble a picture frame:

Mitered corners work well for corner angles at 90 degrees,

like a picture frame. Hard turns cause longer miters, which have too many small

stitches, and shallow turns do not need mitering.

The

simplest form of cornering is to simply turn, with inclinations going around the

turn. When making a hard corner, this results in stitches pivoting around the

inside corner of the turn. If you’re going to turn this way, try beginning to

‘lean’ the stitches into the turn, and when coming out of the corner, give them

some chance to ‘lean back up.’

The

simplest form of cornering is to simply turn, with inclinations going around the

turn. When making a hard corner, this results in stitches pivoting around the

inside corner of the turn. If you’re going to turn this way, try beginning to

‘lean’ the stitches into the turn, and when coming out of the corner, give them

some chance to ‘lean back up.’