Satin columns are versatile objects, and this property page allows

you to use the column in a few styles. “Normal” satin stitches are what you

almost always think of with satins; they go left-to-right and back again, making

a smooth, narrow, continuous stitch. But you also have the option for Contour

and Fringe stitching styles available.

Satin columns are versatile objects, and this property page allows

you to use the column in a few styles. “Normal” satin stitches are what you

almost always think of with satins; they go left-to-right and back again, making

a smooth, narrow, continuous stitch. But you also have the option for Contour

and Fringe stitching styles available.

Pass Count

3 and 5 pass whip stitches are available to create more

texture. The thread does build up, but the program opens the density very

slightly to allow for it. The use case for this is to provide a more vintage, or

even simulating a handmade element in the embroidery.

Satin columns are one of the most-used stitches, and they have

a lot of properties available. The most important of which is the density.

Remember that density is measured in stitch points, which are tenths of a

millimeter. The bigger the distance, the lower the density. Normal density for

satin columns is 4 points to 5 points unless a fine thread and tightly woven

fabric are used. Often, the 5 point density is preferred as it will not push the

fabric around as much, and still provides nice coverage.

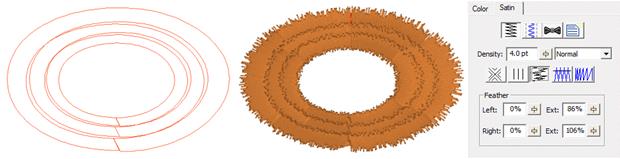

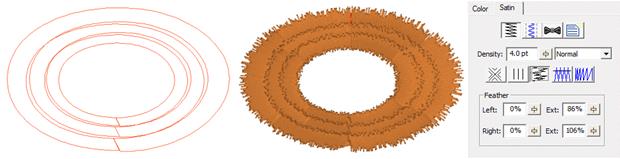

When choosing the patterned topstitch, a normal smooth satin

is the default, however you can adjust the patter to appear like a fill pattern

that curves with the stitching. Each pattern can have its stitch properties

adjusted. Stitch Length in the pattern relates to the size of the pattern that

is made. If you make your pattern too wide, it will not be visible unless the

satin itself is very wide. Here you can see how a satin pattern will turn with

the stitching:

The Edge Pad is a means of protecting the edges of the

stitches from have excessive needle penetrations that can pull on the fabric and

pucker.

When patterning, the needle penetrations can lie next to one

another causing the fabric to lash or even cut. If this is a danger for the

fabric being embroidered, set the “Reverse” to “None” which means the pattern

will only occur on every other stroke of the satin. The pattern effect will be

lighter, but the embroidery will be better and the fabric will not have as many

cuts.

The pattern of the satin also has compensation and gradient

properties. Please refer to the Fill Pattern section of Fill Objects for images

and further description.

Compensation

Left: Level 1 & 2, Right: Level 3

Compensation helps create embroidery that matches the image,

understanding that the process of sewing the design will create distortion as

it is happening. With compensation, the endpoints of the lines in a fill are

stretched out slightly past the edge of the shape. This helps with registration

issues because as the lines are sewn, the fabric is pulled in slightly

(shortened), so the longer lines will reach the spot intended to be covered.

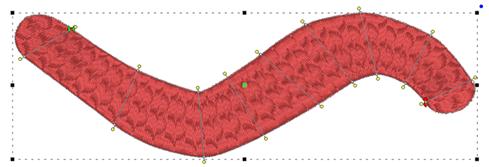

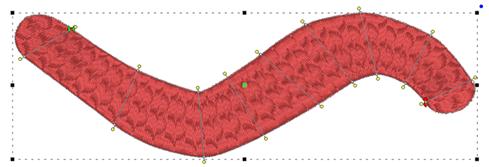

You can use a minimum value, usually 0 – 3 points,

depending on what the fill is lined up against. If your fill has a wide

difference in the width of the runs, in other words some narrow parts and some

fatter parts, you may want to use a percent for the compensation. We

suggest keeping it a small value, 2-3%. It will be kept in check by the Max

value though, even if you use a high percentage.

While the compensation numbers sound like something you should

use, they’re really there more for the professional who uses them all the time.

Most of the time, simply adjusting the shape to overlap anything that neighbors

it will do a fine job of handling registration issues.

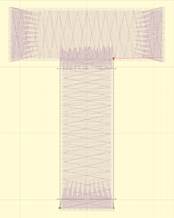

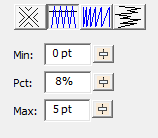

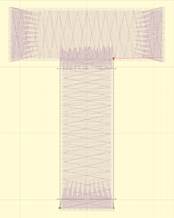

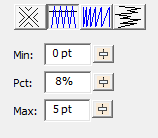

Feathering the edges of satin columns is a good way to

simulate animal fur. Overlap multiple layers to make a more realistic

appearance. In this example, three satin rings were set with feathered edges.

The rings sewed outer-to-inner, and overlap slightly.

Split

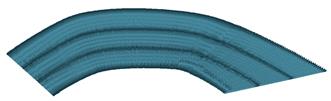

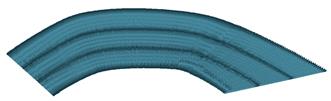

A split stitch in the column simply means that the needle will

land in rows, lengthwise along the column. You can set the number of split

columns, the minimal stitch value (to avoid fabric cuts) and you can avoid the

reverse stitch pattern, which helps preserve the look of the satin column. Here

is a column split into three:

Satin stitches are good at covering the fabric, but they have

challenges, especially along the edge, where tightly placed dense stitches can

penetrate the same hole in the fabric or even cut the fabric. You may have sewn,

for example a knit shirt, and had the edges of satin stitches create holes in

the fabric. For this reason a parallel or zigzag underlay is often used. It

provides coverage while pulling the fabric at slightly different angles and that

can allow the top stitching to have reduced density.

Satin stitches are good at covering the fabric, but they have

challenges, especially along the edge, where tightly placed dense stitches can

penetrate the same hole in the fabric or even cut the fabric. You may have sewn,

for example a knit shirt, and had the edges of satin stitches create holes in

the fabric. For this reason a parallel or zigzag underlay is often used. It

provides coverage while pulling the fabric at slightly different angles and that

can allow the top stitching to have reduced density.

Satin also has the issue of tension. Short stitches in the

same direction, laid next to each other, builds up stress in the fabric,

gathering it in toward the middle of the satin stitch. This can cause

registration issues with subsequent stitching. This can be managed by binding

the stabilizer to the middle of the satin with a center run, or a pair of edge

runs that travel just inside the shape. The edge runs also have the added

benefit of lifting the edges of the satin up, out of the pile of the fabric. For

these reasons it is not uncommon to use a medium density satin with a lot of

underlay.

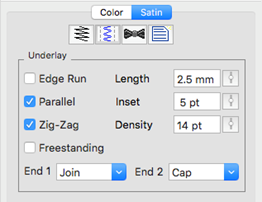

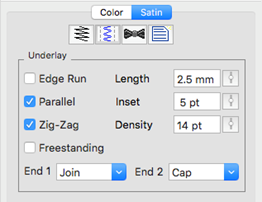

In the underlay properties, the “Edge Run” will create runs on

either side of the satin, just inset by an amount controlled by the Inset field

on the property page. The inset for the edge run is usually is set to fall just

inside the stitching – perhaps a half-needle with or slightly more, which allows

some relief around tight corners. The stitch length of the edge run is also

adjustable; use smaller stitches for tight, narrow columns and longer ones if

you want to reduce the stitch count, or are worried about cutting the fabric.

The default is usually sufficient though.

The density of the parallel and zigzag underlay is adjustable

for increased coverage. Sometimes it is better to have a higher density underlay

(0.8 – 1.2mm) and a lower density top stitch (0.8mm) so that the coverage is

solid, but the pull on the fabric is reduced, which helps with registration

issues (eliminating gaps between stitched areas).

The ‘Freestanding’ underlay creates a mesh under the satin,

similar to the freestanding background object type. This is useful when making

Richelieu bars or satin shapes that will be stitched on wash-away stabilizer.

When using the ‘Freestanding’ option, you do not need the other options, so you

can leave them off. The Length, Inset and Density properties do not apply to the

‘Freestanding’ option.

Foam (3D) Underlay (Level 2)

The ‘End 1’ and ‘End 2’ underlay properties control automatic

caps and joins for 3D foam embroidery. End 1 is defined on the outline as the

location of the closing point (red node).

Note: Because the density required to cut foam cleanly is so

high, avoid turning tightly, as those stitches can bunch up.

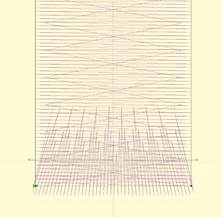

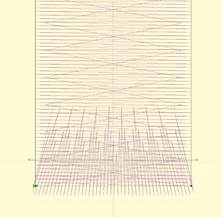

Automatic underlay shown, left-to-right: cap, join, a

letter.

Foam (3D) column style(Level 2)

The ‘Foam’ style automatically sets the underlay,

including end caps on both ends, sets compensation and increases the density so

that the 3D foam can be cut out by the needle.

Contour (Level 2)

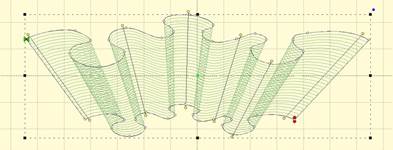

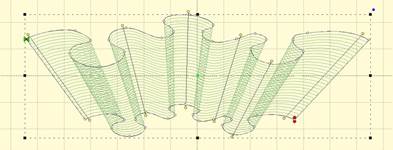

Checking the ‘Contour’ button on a Satin Column will arrange

the stitches to run opposite to the inclinations, rather than parallel to them.

The density is maintained throughout the column, even if the column widens and

narrows, as the program will automatically adjust the number of rows as the

width changes. Contour 2 will provide more of a ‘fill’ effect as areas widen and

narrow, whereas Contour will have varied density across the shape as it

widens.

The Fringe stitch is a unique stitch that allows you to create

what some call “3D Embroidery” by cutting the bobbin threads under the satin,

which frees up one side of the stitching to come up and away from the

fabric.

This Fringe stitch lays a run down along the edge of the satin

first, and then places the satin over top with extra needle penetrations causing

the satin to anchor itself to the run. It finishes off with a top stitch run to

anchor it all together. This method allows you to have fringe effects in

embroidery without the need to anchor the stitching down with a fill, as has

always been the case.

Satin columns are versatile objects, and this property page allows

you to use the column in a few styles. “Normal” satin stitches are what you

almost always think of with satins; they go left-to-right and back again, making

a smooth, narrow, continuous stitch. But you also have the option for Contour

and Fringe stitching styles available.

Satin columns are versatile objects, and this property page allows

you to use the column in a few styles. “Normal” satin stitches are what you

almost always think of with satins; they go left-to-right and back again, making

a smooth, narrow, continuous stitch. But you also have the option for Contour

and Fringe stitching styles available.

Satin stitches are good at covering the fabric, but they have

challenges, especially along the edge, where tightly placed dense stitches can

penetrate the same hole in the fabric or even cut the fabric. You may have sewn,

for example a knit shirt, and had the edges of satin stitches create holes in

the fabric. For this reason a parallel or zigzag underlay is often used. It

provides coverage while pulling the fabric at slightly different angles and that

can allow the top stitching to have reduced density.

Satin stitches are good at covering the fabric, but they have

challenges, especially along the edge, where tightly placed dense stitches can

penetrate the same hole in the fabric or even cut the fabric. You may have sewn,

for example a knit shirt, and had the edges of satin stitches create holes in

the fabric. For this reason a parallel or zigzag underlay is often used. It

provides coverage while pulling the fabric at slightly different angles and that

can allow the top stitching to have reduced density.